“Friendship is a sheltering tree.” — Samuel Taylor Coleridge

“Blessed is the man who trusts in the Lord, whose trust is the Lord. He is like a tree planted by water…” — Jeremiah 17:7-8

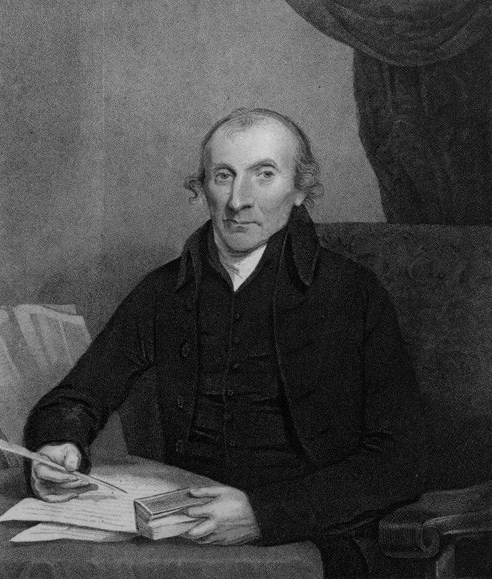

The vital need for a biblical worldview is apparently a battle each generation must fight. Thomas Hartwell Horne was born to fight that battle. Hartwell University is partly named after him (for more on this, see the meaning of our name). Horne’s birth happened in England on October 20, 1780. He was the eldest child in a family of humble means. In the same year, France lent it’s support to the American Revolution, ultimately helping to secure victory for freedom’s cause.

Revolutions in the era of aristocracy held an element of backlash to the “divine right of kings,” a doctrine held by most European royalists—including Marie Antoinette and Louis XVI. This belief claimed that a monarch was above any earthly authority and was therefore above the people and the law. Because the Enlightenment in France got rid of religion and the Bible—the basis for the law—the mob ruled when the monarchs died. Removal of absolutes gave way to the whims of whoever held power at the moment. The Reign of Terror happened because the rule of law was not given its proper place, neither in monarchs nor mobs. “Where there is no revelation, the people cast off restraint; but happy is he who keeps the law” (Proverbs 29:18 NKJV).

Also in 1780, Empress Maria Theresa of Austria, whose sixteen children held significant sway in European courts, died. Her passing gave way to her son’s implementation of the Enlightenment principles sweeping Europe. These same principles led, in part, to the beheading of her unpopular daughter, Marie Antoinette, and the subsequent Reign of Terror in France. This was exacerbated by the peasant’s severe hunger and economic woes brought on, largely, because of the debt France accumulated to defend America.

In the land of Horne’s birth, Oliver Cromwell (1599 – 1658) stood firm against the “divine right of kings” and brought an end to that notion there by signing the death warrant of King Charles I for the “High Treason and other high Crymes” against his own subjects. This ultimately led to limited power in the monarchy and a shift from despotism toward the consent of the governed through parliamentary rule. Somehow, King George III hadn’t gotten Cromwell’s memo when it came to his tyrannical reign over British colonies. Lawlessness clearly remains “at work” in our own time as well (2 Thessalonians 2:7).

Cromwell believed “civil government and social life alike should be based upon the Commandments set forth in the Bible.”[1] “Thou shalt not steal” could have been useful in the Bourbon courts, as well as “thou shalt not murder” for the mob during the Reign of Terror. As a Puritan, Cromwell believed covenant should govern civil society. The Mayflower Compact in 1620 is a prime example of Puritanical covenant for self-government. This document, along with the Magna Carta, is directly tied to the social contract that is the U.S. Constitution. Each of these profound documents are rooted in the Mosaic covenant—the Bible.

1780 was also the year that the indigenous cacique, Túpac Amaru II, instigated a revolution in Peru to overthrow Spanish colonial rule there. He was captured, tortured, and brutally executed in the main square of Cuzco; the rebellion quashed by the powerful Spanish overlords.

All this to say, revolution was the backdrop of Thomas Hartwell Horne’s birth and life. He was presented with two philosophies—two trees, if you will. On one hand, there was the godless philosophy of the Enlightenment which had enough elements of truth to make it a tempting counterfeit. On the other hand, there was God and the Bible. “I set before you life and death, blessing and curse. Therefore choose life, that you and your offspring may live” (Deuteronomy 30:19 ESV). Thankfully, when presented with each of these, Horne chose life.

The Younger Years

Thomas’s father, William Horne, was the son of a village tradesman in Eversley, Hampshire. Despite his meagre living, he did his best to procure an excellent education for young Horne. Between the ages of six and seven, Thomas attended a boy’s school in London where he started to learn Latin and grammar. In the fields surrounding Foundling Hospital, his father would walk early in the morning with him to assist in his lessons. Foundling Hospital was only for children whose fathers were either deceased or had abandoned their mothers and them. It was the source of inspiration for some of Charles Dickens’ characters.

Between the years of 1789 and 1795, Horne “received the rudiments of a classical education”at the charity school, Christ’s Hospital.[2] At the time, Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772 – 1834) was a senior scholar at Christ’s Hospital and gave Thomas private lessons in the Greek alphabet, among other disciplines, during the summer of 1790. Coleridge made frequent visits to the Horne household, accompanying Thomas on holidays. His kindness in teaching Thomas was in gratitude for the hospitality of the Horne family. [3]

Thomas’s daughter, Sarah Anne Cheyne, writes that Coleridge was “an orphan with scarcely any connections in London.”[4] While it is true that Coleridge’s father had died when he was nine, his mother and a great many of his siblings were still living (he was the youngest of ten children). Coleridge, however, wrote that his family caused him nothing but misery and he apparently had a very cold relationship with his mother. Perhaps he told the Horne family he was an orphan as to avoid the painful topic. Upon the death of his father, Coleridge’s mother sent him to Christ’s Hospital as a “charity student.” In an 1801 letter to his friend, Thomas Poole, Coleridge wrote about his family, “I have no recollections of childhood connected with them, none but painful thoughts in my after years.”[5] Upon the death of Poole’s mother, Coleridge wrote of her, “She was the only being whom I ever felt in the relation of Mother.”[6]

The violent temper of the headmaster at Christ’s Hospital was hard on Coleridge’s sensitive temperament, and the kindness of Mr. Horne must have been like the “sheltering tree” he would later write about in his poem, “Youth and Age.”

In June of 1793, Thomas’s father, William Horne, died at the “early age of thirty-six.”[7] At twelve years old, Thomas was left as the eldest of six orphans. His mother died two years prior as she was giving birth to her sixth child. While relatives helped as they could with the younger children, Thomas put his education to work in assisting “gentlemen of the law.” Someone had given him the money he needed to buy a pen and paper, which he used to gain this first employment. His small income was enough to keep him on coarse brown bread. To supplement his wages, he began to write literature, his first publication being A Brief View of the Necessity and Truth of the Christian Revelation when he was twenty (an essay he had written at eighteen).

Thomas had come to a crisis of faith when he read “an infidel novel of French origin.”[8] His essay was the result of being a good “Berean” (Acts 17:11). He studied and found the answers to his philosophical crisis. In the essay,

“[Horne] stepped forward in the defense of our common faith, and to oppose the rapid progress which the disciples of infidelity are making, by disseminating their pernicious principles, particularly among the junior part of the present generation.”[9]

In our present generation, the battle is still the same. We need new men and women to take up the legacies of people like Thomas Hartwell Horne, Oliver Cromwell, G.K. Chesterton, C.S. Lewis, and others. We need keepers and defenders of the faith to arise and “See to it that no one takes you captive by philosophy and empty deceit, according to human tradition, according to the elemental spirits of the world, and not according to Christ (Colossians 2:6-8 ESV).

Horne blazed the trail for modern apologists. Rising early to study before work, Thomas defined diligence and faithfulness. He noted, however, “it is one thing to be speculatively convinced of the truth of Christianity, and another to have it in the heart.”[10]

An Important Change

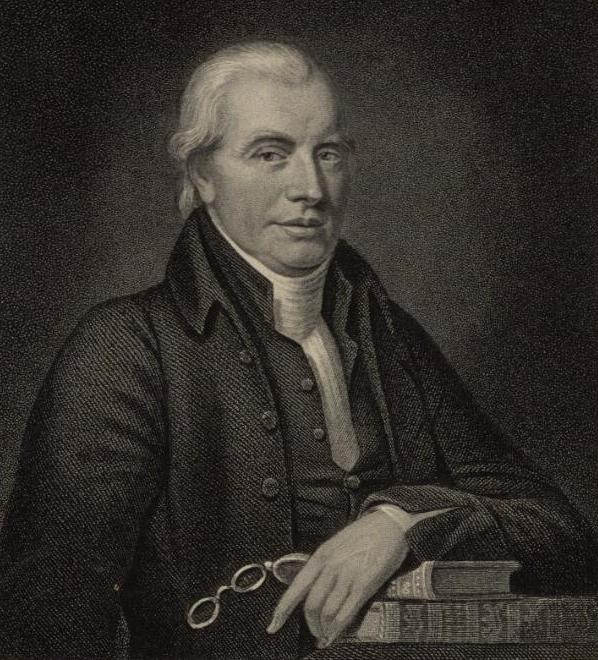

Horne writes, “In 1801…my mind experienced a most salutary and important change.” He was perusing an “eccentric volume which had excited much and most undeserved ridicule of the Wesleyan Methodists.”[11] Horne’s curiosity was awakened, so he went to hear what they had to say. He noted that while others went to scoff, he remained to pray. Notable Methodist leader, Joseph Benson (1749 – 1821), talked about “Christ in you, the hope of glory” (Colossians 1:27). This message attracted him, so he went again. This time, Thomas was particularly arrested by Benson’s message on “the folly and danger of irresolution in the momentous concerns of the soul.” He said God had apprehended him by Benson’s preaching. Subsequently, he read J.W. Fletcher’s Rational Demonstration of Man’s Corrupt and Lost Estate. Horne said this “brought me a humble penitent to the throne of grace, where I embraced the atonement, found peace, and gave myself to the service of God my Savior.”[12]

Under John Wesley, Joseph Benson and J.W. Fletcher became pillars in the Methodist movement. An interesting note on Benson is that he “had studied at Oxford, but was refused his degree for the offense of visiting poor neglected prisoners in Oxford jail.”[13]

On September 12, 1812, Thomas married Sarah Millard. He called her his best earthly treasure.[14] The two were married for forty-six years and had two daughters, Sarah and Susan. Tragically, Susan died in 1835 from tuberculosis at the age of fifteen.

Biblical Scholarship

Horne’s essay, Considerations on the Probable Causes of the Increase of Skepticism and Infidelity (1802), highlighted one of the causes for disbelief in the Bible as “the false system of education prevailing among professing Christians.”[15] We are facing the same crisis today. At the time of this essay, Napoleon was rapidly rising to power in France and the Enlightenment’s secularism was rampant. Thomas was one of the many volunteers who trained for war in the event of an invasion from France. After the Battle of Trafalgar, he was on duty at Lord Nelson’s funeral.

Horne worked hard to provide for his younger siblings and experienced God’s promise that if you “seek first the kingdom of God and His righteousness, all these things will be added unto you” (Matthew 6:33). He was never wealthy in material goods, but always had enough to live and share. After working to earn a living all day, he would rest for half an hour, take strong tea in the evening, then work far into the night so he could accomplish his own literary work and correspond.

In 1806, Thomas came to work as clerk for Mr. John Butterworth, a wealthy philanthropist who was brother-in-law to the famous Methodist theologian and commentator, Adam Clarke. At that time, Clarke was the president of the Wesleyan Methodist Conference and took a “deep interest” in Horne’s welfare. It was through Butterworth’s connections that Thomas founded the first Bible Association in Lambeth, as well as the first Sunday School in Westminster. At this time, he began to delve deeper into the sacred scriptures than ever before. He had already begun working on a seventeen-year project, which would be the magnus opus of his life: the Introduction to the Critical Study and Knowledge of the Holy Scriptures (1818). This book garnered widespread acclaim and transformed biblical scholarship. In the first edition, he outlined a plan for arranging the books of the old and new testaments chronologically. This helped to unfold the overarching story of the Bible for scholars.

In 1819, Horne published a treatise called Deism Refuted: or Plain Reasons for being a Christian. It sold eight thousand copies within a year and was reprinted in America in 1820. The opening statement of this treatise follows.

“To be a Christian—in other words, to believe the Christian religion—is, to believe that Moses and the Prophets, Christ and his Apostles, were endued with divine authority, that they had a commission from God to act and teach as they did, and that He will verify their declarations concering future things, and especially those concerning a future life, by the event: —in short, it is, cordially and sincerely to receive the Scriptures as the only rule of our faith and practice, as the foundation of our hopes and fears.”

Thomas stressed the importance of the Bible as the basis for the Christian faith. He also understood its irreplaceable value in culture when he goes on to say, “In fact, when I look into the state of the world, in all places where the Bible…has not been known, I am convinced that we are incapable of discovering for ourselves a religion that is worthy of God, suited to our wants, and conducive to our true interests.”

The press called upon Horne to consider secular objections to his works. He spent much time doing this, winning some to faith in Christ. “If there were no genuine coin,” Thomas wrote, “there would be no counterfeits.”[16]

Horne’s growing influence through biblical scholarship and apologetics captured the attention and gratitude of many leaders in both Anglican and Wesleyan circles. The Bishop of London, William Howley, granted him Holy Orders in 1819 because his work in producing the Introduction to the Critical Study and Knowledge of the Holy Scriptures was an ample equivalent for an academic degree, which Thomas did not have. He had been given an honorary M.A. by the University of Aberdeen and Bishop Howley, who later became Archbishop of Canterbury, “placed his name on the books of St. John’s College, Cambridge, where he ultimately proceeded to the degree of B.D.”[17]

Societal Influence

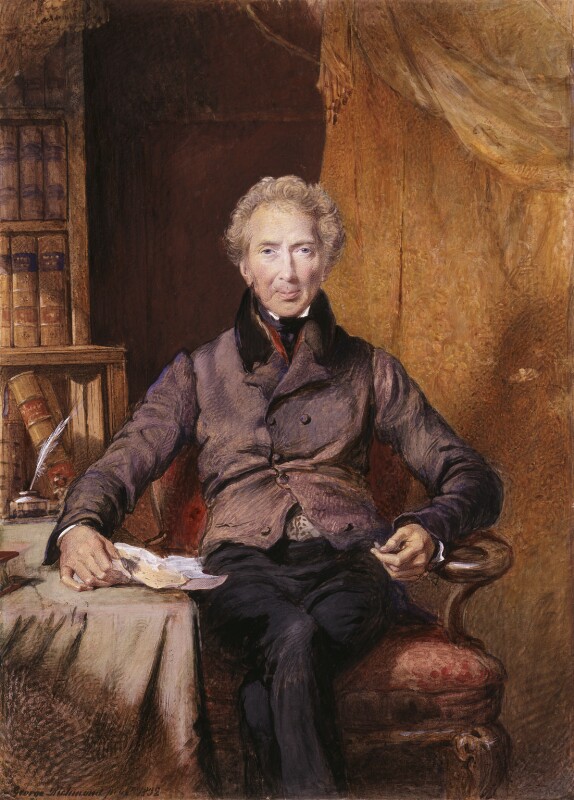

In her biography, Horne’s daughter notes that few of his “own letters are come to hand, because much of his confidential correspondence was carried on with the mutual agreement that letters should be destroyed.” Thomas kept company with the movers and shakers in England. In 1822, he was admitted to the Eclectic Society. John Newton (1725 – 1807), author of Amazing Grace and former investor and captain in the slave trade, founded the society in 1783. Newton was a strong spiritual influence and personal adviser to William Wilberforce (1759 – 1833).

In 1825, Horne joined the Fellows of the Royal Society of Literature. From 1826 – 1833, he was the assistant minister at St. James’s Chapel where giants of history like William Wilberforce attended. Lord Teignmouth, former Governor-General of Bengal (1793 – 1798), also attended St. James at the time. Teignmouth also served as the first president of the British and Foreign Bible Society, which came into existence as the result of William Carey’s Bible translation efforts in India. William Carey (1761 – 1834) is considered to be the father of modern missions.

Like Horne, Wilberforce understood how important the Bible is as the guidebook for society. He pointed out that slaveholders twisted scriptures in support of their vile trade. The core principles of Christianity, he underscored, preach love and fairness towards all, making it hard to believe that supporters of the slave trade are genuinely influenced by religious teachings.[18] Wilberforce was also an earnest promoter of Christian missions. He saw Christian missions in British India to be “the greatest of all causes” and considered the mission that William Carey founded there to be “one of the chief glories” of Britain. For more, see The Father of Modern India: William Carey by Vishal Mangalwadi.

The Final Years

Throughout his life, the indomitable spirit and unwavering faith of Thomas Hartwell Horne inspired countless leaders, ministers, and laypeople. The American Bishop, Philander Chase, said it was Horne who stirred him to start “a college for the education of clergymen from among the natives of Ohio.” This became Kenyon College, the oldest private institution of higher education there.[19]

Thomas’s wife passed into eternity on July 7, 1858, in her seventy-fifth year. This was said to be his “severest earthly sorrow.” His strength soon began to fade until he was no longer able to preach or write in defense of the Christian faith. In a final letter to his grandson, he wrote:

“Daily and fervently implore the Divine blessing, and ‘then continue in these things,’ as St. Paul wrote to his son Timothy. It was by the union of prayer, faith, and study, under every disadvantage that I was enabled to produce my ‘Introduction.’”[20]

In November 1861, Thomas wrote:

“I have now entered on my eighty-second year. My greatly impaired health, and far advanced years, tell me to arise and depart for this is not my rest (Micah 2:10), and that I am living only day to day. During my long career I have found the Christian life to be a warfare: yet I desire to record it to the praise of Divine grace, that, ‘In the multitude of sorrows’—personal, relative, literary, and pastoral.—’Thy comforts’ (O Lord!) ‘have refreshed my soul’ (Psalm 94)… I am now ‘waiting all the days of my appointed time, until my change come’ (Job 14:14).”[21]

While volumes could be written about Horne’s incredible journey and contributions, one sentiment remains clear: The “warfare” he waged through his unparalleled biblical scholarship and apologetics has fortressed the foundations of the Christian faith. Reverend Joseph B. M’Caul[22] said of him, “The palace, whose turrets serve as landmarks to the pilgrim, is founded in the dust.” This was Horne. From humble beginnings, he erected biblical landmarks as the guideposts to faith and godly society. A biblical worldview resulting in the rule of law holds back the Reign of Terror. Just look around today and see what is happening everywhere the Bible is mocked. In the poetic words of Coleridge, Thomas Hartwell Horne was truly “a sheltering tree.”

[1] See Oliver Cromwell by Theodore Roosevelt.

[2] Reminiscences, Personal and Bibliographic by Thomas Hartwell Horne’s daughter, Sarah Anne Cheyne, chapter 1.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Collected Letters of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Vol. 2: 1801 – 1806, edited by Earl Leslie Griggs, page 756.

[6] Ibid., page 758.

[7] Reminiscences, Personal and Bibliographic, chapter 2.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Reminiscences, Personal and Bibliographic, chapter 4.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Reminiscences, Personal and Bibliographic, chapter 5

[17] Ibid.

[18] See A Letter on the Abolition of the Slave Trade by William Wilberforce (1807).

[19] Reminiscences, Personal and Bibliographic, chapter 6.

[20] Reminiscences, Personal and Bibliographic, chapter 15.

[21] Ibid.

[22] M’Caul was Chaplain to the Lord Bishop of Rochester, as well as colleague and friend of Horne.